Atmospheric Physicist Finds Weather Data From Ill-Fated Expedition

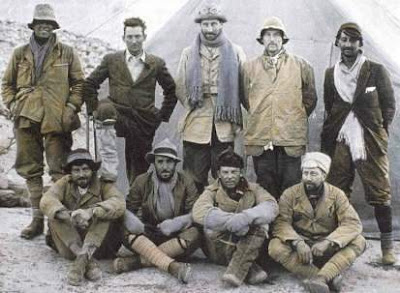

His head bare, arms akimbo, George Mallory looks ready

to take on the mountain that would become his grave.

This was his third expedition to Everest. Andrew Irvine is on the left.

The disappearance of British explorers George Mallory and Andrew Irvine on June 8, 1924, during an attempt to become the first to conquer the summit of Mount Everest, has long been shrouded in mystery. The men vanished during their climb, with few hints as to what caused their demise. The puzzle has bedeviled mountaineers and historians ever since.

But to solve the mystery requires evidence. It was in search of such evidence that G.W. Kent Moore, a physicist at the University of Toronto in Canada, found himself wearing white cotton gloves one morning a few years ago, gingerly picking through an old sheaf of papers at the Royal Geographical Society in London.

During a stopover on his way to a meeting in Norway, the soft-spoken Canadian had a few hours to kill, so he decided to spend them hunting for some weather data from the ill-fated expedition.

Moore found what he was looking for.

"It was one of those moments that doesn't happen very often in your career," Moore told OurAmazingPlanet. "One of those 'Eureka!' moments."

The cause for Moore's excitement was a simple table of atmospheric (or barometric) pressure measurements from the 1924 campaign. It showed that barometric pressure dropped precipitously in the days leading up to June 8, the day that Mallory and Irvine disappeared. To Moore, an atmospheric physicist who studies the behavior of pressure systems at high altitudes, this pressure drop indicated one thing: Bad weather. Very bad weather.

Secret Superstorm

When barometric pressure in an area drops, air from surrounding areas rushes toward the low-pressure region. All that air has to go somewhere, Moore said, and it usually goes up, producing stormy weather.

Further analysis of the newly unearthed data, in conjunction with modern atmospheric pressure data and Indian meteorological maps from the time period, seemed to confirm Moore's initial hunch.

On the day that Mallory and Irvine disappeared, it's possible that a furious storm raged on Everest's 29,000-foot zenith — a storm similar in strength and fury to the infamous storm that killed eight people atop the mountain in 1996, an event described in Jon Krakauer's account, "Into Thin Air." Data reveal nearly identical drops in barometric pressure on the two days.

This 1909 photo shows British mountain climber George Mallory,

who died while scaling Mount Everest in 1924,

on the Moine ridge of the Aiguille Verte mountain in France.

However, conditions on the mountain can vary wildly, depending on elevation. What an individual experiences at 24,000 feet — the altitude of Camp IV, one of several stopping points along the traditional climbing route — can contrast with what someone at the top might see at the same time. What Odell experienced as a brief interlude of snow and sleet could have been far different for Mallory and Irvine, several thousand feet higher.

"It's enough of an elevation change that the weather can be very different," said Garrett Madison, an expedition manager for the mountaineering outfit Alpine Ascents International, and a seasoned climber who has scaled Everest three times.

Hard To Catch A Breath

A drop in barometric pressure doesn't just create dangerous storms, it also reduces oxygen levels. Near Everest's summit, oxygen levels are already barely high enough to sustain life; any additional drop could have made breathing extremely difficult, said John L. Semple, chief of surgery at Women's College Hospital in Toronto, Moore's co-author on a report of the recent findings, and himself an avid mountaineer who has tended climbers on Everest.

Lack of oxygen causes swelling of the brain and can lead to confusion, an undesirable condition in any environs, but particularly in a harsh environment where just one misstep can spell disaster.

Mallory's body was discovered in 1999. Preserved by the cold, dry mountain air, there were still dark contusions and gashes visible in his flesh, indicating he'd probably fallen. He was face down, his arms raised above his head, fingers dug into the surrounding scatter of rocks, as though clinging to the side of the mountain. Irvine has never been found.

It is still unknown whether the men ever reached the summit. Humans wouldn't finally conquer the mountain until nearly three decades later, when New Zealander Edmund Hillary stood atop the unforgiving peak for the first time, in 1953.

And although the mystery of precisely what befell Mallory and Irvine remains, "it's great to have the opportunity to contribute to the big picture of what actually happened on that day," Semple said.

The study summarizing Moore's and Semple's findings is published in the August edition of the journal Weather. Historical photographs for this story were provided by The Bentley Beetham Trust.

NR

© 2010 The Esoteric Redux. All Rights Reserved